Digital Memory Archiving: The Oral Narratives by the Residents of Karantina

Working with or in the archive is already a contested realm, even before the rise of the digital age. The latter has altered our perception of the archive. The nomological1 understanding of the archive is provoked and re-questioned vis-à-vis the internet, consequently opening the doors for a multiplicity of archives to emerge. It also provokes the role of the archivist and re-defines it. In the absence of the digital, oral narratives as a form of archiving remain a form of remembering.

This essay reflects on the project “Oral Narratives by the Residents of Karantina” conducted by the Beirut Urban Lab under the umbrella of the Imagining Futures. It is part of a greater project on the urban recovery of Karantina carried out in response to the Beirut port blast of 20202 and reflected on in volume A3. The essay raises questions related to the role of digital tools in facilitating egalitarian archiving, issues of authorship, the role of the archivist and even his death. The proposition “death of the archivist” is coined after the Roland Barthe’s “Death of the Author” implying that textual meanings were never under the authorship of the author/archivist. The latter is a mediator, and texts constantly alter their meaning with reference to the reader, or to other texts. Similarly, the death of the archivist proposes a new role, that of a facilitator, in order for an eruption of meaning to occur, in the psychoanalytical sense of the term. The essay also re-questions some fundamental notions regarding the location of the archive and its accessibility, especially under the digital realm, surpassing a major dichotomy, where oral narratives published online are nowhere and everywhere simultaneously. The essay neutralizes the role of archivist who channels people’s narratives, thus rendering the archival practice and power to the narrator.

Karantina is a site of multiple traumas and remains one of the most marginalized and vulnerable neighborhoods in Beirut that houses low-income groups. It is confined by natural and physical infrastructural edges that separate it from the city. Karantina’s built environment is an overlap of historical evolution, spatial practices, and built fabric, further damaged by the Beirut port’s blast. Sitting at the eastern edge of Beirut, Karantina has minimum archival material with respect to other parts of Beirut4. However, both Karantina and Beirut suffer from collective amnesia, especially that the collective memory of the city is capitalized, institutionalized and forced as a collective narrative on a whole nation. Today, Karantina is stigmatized, silenced and excluded from participating in the narrative or future of the city.

Figure 1. Abandoned Houses, Karantina, Beirut, 2022. Taken by: Leyla El Sayed Hussein

The “Oral Narratives by the Residents of Karantina” is a digital platform that contains georeferenced stories narrated by the residents of Karantina. The georeferencing acknowledges spatialized memories connecting people to place. It also acknowledges Karantina’s urban transformation, accounting for both standing or erased sites of memory. It thus identifies places of memory that no longer exist due to spatial erasure. Furthermore, georeferencing show that same site can have multiple narratives. These stories intersect with images and hyperlinks that are anchored on an interactive map of Karantina and its wider context. The aim of this project is to build the oral archives of Karantina’s residents heading towards an imagined future; one that is linked to recovery. It also aims to register the memory of the marginalized residents of Karantina without altering it. The participants remained anonymous and there was no imposed or prescribed topics. One question was circulated among 100 participants; the question was: “how do you narrate the history of Karantina”? As a first observation, some common themes started emerging among the participants, mainly revolving around the war, the sea, the slaughterhouse and the highway5. Initially the platform was intended to organize the narratives by themes. However, this process of classification and sorting resonated with a noticeable interference of the archivist, triggering a re-questioning of the archivist’s role. Therefore, to neutralize the agency of archivist, the stories were organized against a more neutral system and kept as per alphabetical order of the participants’ initials. Later the themes explored where added under the initials. The multiplicity of narratives reflected in this project, especially referring to similar themes, are testimony for plurality.

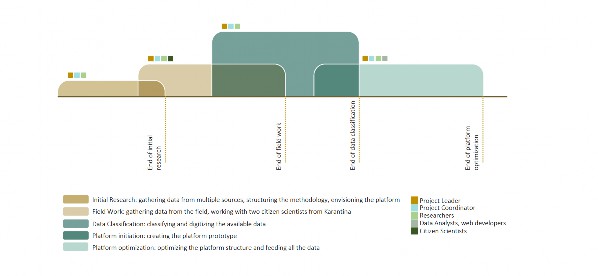

Figure 2. Diagram showing the project's different phases. The methodology of work was spread into 5 phases, starting by the initial research and envisioning the platform as well as situating it within a theoretical framework, then doing an extensive field work to gather the data, classifying it, initiating the platform, and then optimizing it.

The team embarked on building this specific type of Karantina’s archives as part of archiving the city from the margins and through the voices of its marginalized citizens. The outcome of the project was a digital online open-source platform for Karantina. It offers georeferenced oral narratives collected by the research team to facilitate for the community members and stakeholders across generations, gender, and class to browse archival material such as photos, maps, and oral voice bites. The research team conducted and registered 100 oral narratives, with the help of trained Citizen Scientists6 (CS) who are residents of Karantina.

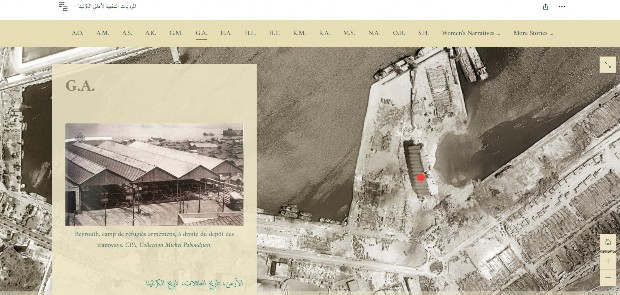

Figure 3. Platform Interface, showing the main story board along with the assigned locations on the map: The Silos of the Port of Beirut, post-blast.

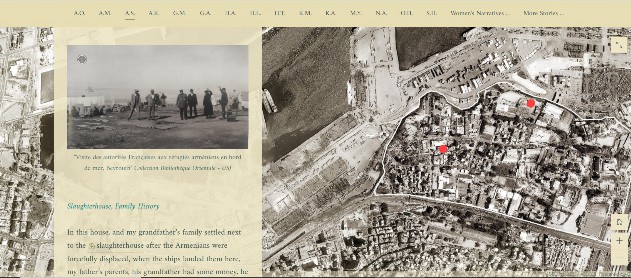

Figure 4. Platform Interface, showing the main story board along with the assigned locations on the map: The slaughterhouse located in the neighborhood of Karantina.

One of the aspects investigated here and relating to the nature of the archive, is the language used to build these data layers. To make the platform more accessible to different users, all voice bytes were transcribed in Arabic, and translated to English as accurately as possible. The hyperlinks related to specific sites on the map were also attached to both texts, the Arabic and English ones. A sample video of the platform can be accessed using this link.

The multiplicity of narratives reflected in this project, especially referring to similar themes or events, invites one to reflect on the type of the archive we are setting the platform for. It can be argued to be a ‘memory archive’. While the classification of the archive is perceived as a static with a certain order, in this specific type of archive proposed in this project, memory seems to function differently. The ‘memory archive’ is a term that we propose, and that erupts to describe the complex layering of language, memories, images, and the city. As Edward Casey elaborates, “These various differences point to a larger truth: the mansions of memory are many” (Casey, 2010, p. x).

Intuitively, the word archive refers to tangible objects or documents relying in the past, while the word digital archive refers to intangible material hinting to a future. While other models of archiving practice a political role over the archive, such as: what gets archived and what not, our project’s open source digital archives did not go into the process of sorting, selecting and excluding material. This is also enhanced by the abundance of storage that digital platforms offer. In this project, traces of the past were narrated by different participants. Chunks of stories relating to the sea, to the war, to Karantina, and to the city in general, are there divided and sorted by the participants only. Here, the oral narratives, although mapped on a digital platform, resonates with an authenticity that is old and primary, since language is the rawest and most primary forms of narration. The produced archives becomes a raw memory untouched and unfiltered, and most importantly unselective. By that, participants can claim their authorship over this specific memory archive. We argue that this project manifests how memory operates in oral narratives during the process of archiving the city, with the agency of the archivist neutralized. And this is specifically why, this project can be a step towards a future the narrators wish to imagine.

Digital archiving aims at a more egalitarian archiving of the city, which opens ways for future imaginaries. Not only does it allow participants to freely narrate, but it also gives users of the platform a flexible access. It opens a wide range of flexibility to re-use the data and re-interpret it, a sort of a grand door inviting any visitor, or researcher, towards a future “un-archiving” of the digital archive produced. Moreover, it facilitates channels for an eruptive narrative to occur through the stream of language with no a priori expectations or goals. By reducing the role of the archivist, the platform challenges authoritarian narratives by exploring alternative and inclusive egalitarian methods of archiving its oral history and socio-spatial practices from the margins. This form of archiving allows narrators to be the archivists of their own narratives, expands the role of the archivist, and increases the egalitarian nature of the project to break the power dynamic between the archivist and the participants. More importantly, it reframes the role of the archivist as a facilitator for these narratives to erupt.

This project reveals narratives that remained unheard and maybe unsaid in one of the most secluded neighborhoods of the city. Through enhancing equal access and anchoring the oral narratives in time and space, this project reclaims the absence of Karantina’s narratives and anchors them in the city’s archives. The project proposes an alternative archival form that transforms the oral narratives of Karantina’s residents from a mode of remembering into a mode of registering.

In 1999, Marie-Anne Chabin7, published a book entitled “I think, therefore I archive”, in which she discusses the fate of the archive within the digital realm. The title of her book implies immersing the humankind in a grand archive, hinting to a colossal container where the archive is constantly expanding. Projecting this book title on our case study, can we claim the following: “I narrate, therefore I archive”? On the very first day of initiating this project, in a calm street of Karantina, when asked about narrating the history of the city, an old man stated: “I am the Archive”.

Notes

1 The nomological meaning the law behind things or subjects, denoting a certainty is re-questioned.

2 On August 4, 2020, Beirut witnessed one of the largest non-nuclear explosions in history. The explosion killed over 218 people, wounded 7000 people and damaged half of the city. (Human Rights Watch, 2021)

3 Refer to the essay entitled “Recovery as (Un)archiving: The Case of Karantina following the Beirut Port Blast” in Volume A.

4 During the research on Karantina across different projects, we looked into multiple archives, coming from different but mostly private sources, including (The Archives and Special Collections, 2024) of the Jafet Library, at the American University of Beirut, such as the old photographs collections of the Bonfils Collection and the Moore Collection, rarely clear photographs of Karantina were found. Even in archival material such as historical maps that were found, the neighborhood of Karantina was partially cropped.

5 The war: mainly referring to the Lebanese Civil War between 1975 and 1990.

The slaughterhouse: Karantina is known for hosting the Beirut’s slaughterhouse.

The highway: referring to the Charles Helou highway, built circa 1956-1959, which secluded Karantina even further from the rest of the city.

6 The recovery team at the Beirut Urban Lab previously trained twelve citizen scientists residing in Karantina in research methods and data collection. Two citizen scientists were part of the research team for this project.

7 Marie Anne Chabin is a French archivist specialized in records and data management and information.

References

Casey, E. S. (2010). Remembering: A phenomenological study (Second edition). Indiana University Press.

Human Rights Watch. (2021). They Killed Us From The Inside: An Investigation into the August 4 Beirut Blast.

The Archives and Special Collections. (2024). https://www.aub.edu.lb/Libraries/asc/Pages/default.aspx